Moving beyond a single measure of a school

iStockphoto.com

iStockphoto.com

iStockphoto.com

iStockphoto.com

Editor's note: California officials are at a turning point as they begin a lengthy process of replacing the Bookish Operation Index with a new system of measuring school and commune performance. In this background report, EdSource editor-at-big John Fensterwald explains what the transformation might wait like from the perspectives of key players involved.

The State Lath of Teaching is seizing the hazard to redefine pupil accomplishment and reframe how schools are held accountable for performance. It is in the throes of replacing the Bookish Operation Index, the three-digit number that has been California's narrow judge of schoolhouse progress for a decade and a one-half. The question is, what will take its place?

Fully rolling out a new accountability system is projected to take three years – in that location is no legislated deadline. But land board members and others who accept shared their thoughts have expressed similar concepts of what information technology might – and should not – be.

At that place is near-universal agreement amid educators and policy makers that a new organisation should be distinctly unlike from the API, which is calculated by weighting school and commune scores on diverse subject area assessments. Instead of a single number with consequences tied to end-of-year standardized tests, in that location should exist multidimensional measures reflecting the complexities of school life and functioning, including potentially difficult-to-quantify indicators of school climate, as well as test scores and indicators of success in preparing students for higher and career options. State lath President Michael Kirst uses the illustration of gauges on a car dashboard that brandish oil pressure, temperature, battery capacity and mileage, each measuring different components of a machine's performance.

Although there are shades of difference, state board members and educators mostly concur that school improvement should be the overriding goal of a new accountability system and that schools and districts should exist given fourth dimension and flexibility to achieve specific and clear goals. This approach would dissimilarity with a decade of superlative-down sanctions under the federal No Child Left Behind law, said Rick Simpson, deputy chief of staff for Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins and education adviser to a half-dozen Associates speakers. "Every bit a state, we kind of reached the consensus that the mechanisms of intervention and penalization were non constructive tools for changing behavior," he said.

A new accountability system would culminate a series of celebrated changes that are already reshaping K-12 pedagogy in California. These started with the shift of authority and responsibleness over budgets and policy from the state to local school districts under a new funding system that directed more than coin to low-income children and students learning English. The funding law established Local Control and Accountability Plans, or LCAPs, that crave districts to set goals and steer money to meet broader indicators of school functioning than test scores alone can provide. New academic standards – the Common Core Land Standards and Side by side Generation Science Standards – accept raised expectations and shifted attention to the complex challenges of preparing students to succeed beyond high school.

PACE

Jannelle Kubinec of WestEd explains evaluation rubrics at a conference in Jan sponsored by the research arrangement Footstep.

A new accountability arrangement must necktie these big educational shifts together, says Jannelle Kubinec, who directs the Comprehensive School Assist Program for the San Francisco-based research agency WestEd and also is leading outreach efforts for the land board. "We are at a rare moment of change," she said at a recent conference in Sacramento on the future of school accountability. "If we accident it at present, we are not going to take this opportunity again, at least with regard to aligning policy."

David Plank, executive director of the independent research organization Policy Assay for California Pedagogy, agrees about the magnitude of the potential changes.

"California has embarked on something radical," he said. "The land is moving dramatically from top-down standardized accountability to something with a much smaller state function and a much smaller part for exam scores. Later having spent the last 20 years getting folks to sing from the same hymnal, we're now proverb, 'Do what is best for your district and community.'"

In January, Plank and Stanford School of Educational activity professor Linda Darling-Hammond published a policy paper, "Supporting Continuous Improvement in California's Education Arrangement," that laid out the principles for a new accountability organisation built around the goals of giving districts the flexibility and teachers the resources to create an environment that fosters continuous improvement. Kirst praises the written report for providing a framework for what the organization might look similar while acknowledging it could terminate up looking quite unlike.

For starters, in that location'south no understanding notwithstanding amid key players – groups representing teachers, local schoolhouse boards, members of the country board, legislative leaders and particularly civil rights organizations – on the details. At that place is also no consensus on where to strike a balance betwixt giving districts animate room to improve on their ain and upholding the state'southward obligation to see that all students get the opportunity for a quality education. Finally, there's doubtfulness whether Congress, in rewriting the No Kid Left Behind law – if and when that happens – will give states the flexibility to devise their own approaches to accountability that California is counting on.

Plank said that in the decades earlier the advent of a land-based accountability system and No Child Left Backside, "there was a long history in which local command worked to the detriment of poor and Latino kids." Advocacy groups are concerned that if turned loose, "districts will screw kids once more," he said. "Then there are people like me who say, 'I have seen generations of policy failure (under prescriptive country and federal mandates), so information technology's time to try something different.'"

The country API and the No Child Left Backside law are both test-based systems. The API was created in 1999 to make up one's mind which schools deserved extra money through the Governor's Operation Awards and which needed state oversight through the Immediate Intervention/Underperforming Schools Plan. The state suspended both programs afterward a few years but continued to calculate an annual API. Penalties under No Child Left Behind accept been meted out to schools and districts based on percentages of students who failed to attain proficiency, mainly on state English language arts and math tests. Sanctions include giving students the right to attend better-performing schools and setting aside a portion of a school's federal money for tutoring.

Many dimensions to a school

The state lath is not starting from scratch in designing a new organization. In the 2022 law establishing LCAPs, Gov. Jerry Brown and legislative leaders signaled they favored a multidimensional approach. They created eight priority areas for schoolhouse improvement that the LCAPs must address and two dozen sources of data that districts must use to rail progress. The priorities include student appointment, as measured by heart and high school dropout rates, attendance rates, absenteeism and graduation rates; school climate, as measured past suspension and expulsion rates and student surveys; implementation of standards, including Common Core; and pupil achievement. Metrics for the latter include rates of reclassifying English learners every bit proficient in English language and passing Avant-garde Placement exams, scores on standardized tests, and, finally, a schoolhouse's API scores. Lawmakers assumed the API would continue to exist when they wrote the law.

Step

Rick Simpson and country board member Sue Burr discuss the future of accountability at a conference sponsored by Policy Assay for California Education in Sacramento in January.

Listing ii dozen metrics that districts must rails in their LCAPs does not by itself constitute a state accountability system that sets compatible targets for achievement and consequences for failing to come across them. The Legislature, withal, did rough out a structure for one and gave the state board the job of fleshing it out. It will begin to take shape over the next year every bit the lath addresses three problems: the hereafter of the API, evaluation metrics and the function of the new country bureau formed to monitor improvement and oversee assistance for persistently troubled schools.

The futurity of the API

This spring, parents and schools will receive the results of standardized tests on the Mutual Cadre standards in math and English language arts. The state lath must decide whether test scores, cleaved down past school and student subgroup, should stand on their own as one component of the new accountability system. Or the lath could give the scores more prominence through a reconstituted API that would somewhen incorporate yet-to-exist-developed tests in scientific discipline and social studies, a high school go out exam aligned to new standards and perchance career and college readiness indicators.

A land advisory committee is recommending replacing the API, and Plank besides favors eliminating information technology, to end what he views as the distorted power that legislators and realtors (who price houses based on a neighborhood school'southward API) give to an imperfect, one-dimensional measure of achievement. But that won't exist piece of cake or non-controversial. The API is embedded throughout land education laws, and the Legislature might have to rewrite or expunge them. That won't happen this yr, Kirst said. In a letter to the country board, a coalition of two dozen ceremonious rights and children's advocacy organizations said they favor keeping the API "to ensure California will have in place a single coherent system of support, assistance, and intervention."

Terminal year, the state board suspended the API then that school districts could focus full attention on implementing the new Mutual Core State Standards and preparing for new computer-based Smarter Balanced tests on the standards that students will take this jump. The Legislature has given the lath the choice of suspending the API a second year also. At that place's a good gamble that the board volition do and so when it meets on March 11 in order to purchase more fourth dimension for statutory changes.

How many metrics?

The Legislature recognized that an accountability arrangement needs a refined set of tools, so it gave the country board until Oct. 1, 2022 to create a set of "evaluation rubrics" that fulfilla broad fix of purposes. The law says the state board should set performance targets and goals for improvement for all of the metrics that utilise to each of the 8 LCAP priorities. The board would gear up, say, a statewide target that threescore percent of loftier school seniors would pass the fifteen courses, known as A-Yard, for access to the Academy of California or the California State University systems; currently about forty percent of seniors satisfy the A-G course requirement. The board would and then list the expected rates of improvement for districts, schools and a dozen educatee subgroups.

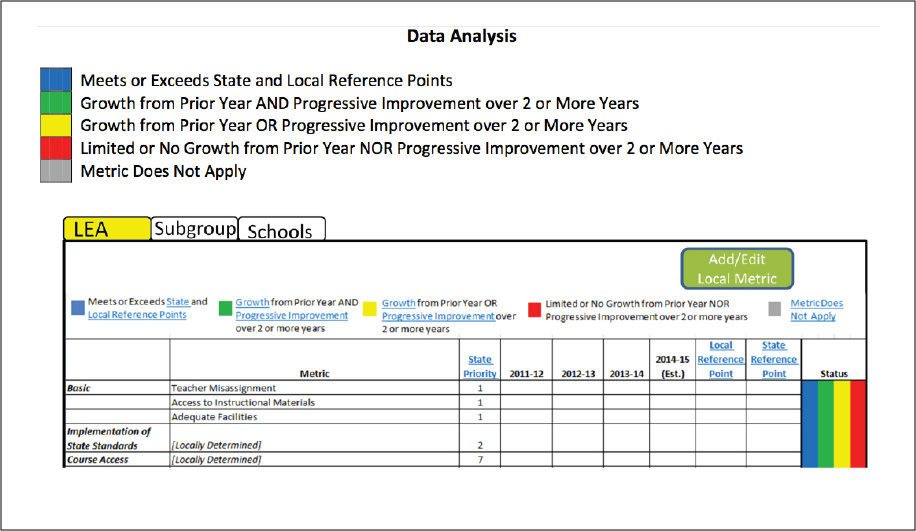

Since last fall, Kubinec of WestEd has been meeting with education groups and holding public meetings across the state to gather views on the evaluation rubrics. Concluding Friday, as part of the state board's calendar for the March meeting, WestEd released a draft of what the evaluation rubrics might wait similar (see a sample from page viii of the draft, beneath). The organization and brandish of the data are patterned afterwards the accountability system used by the Canadian province of Alberta.

Credit: WestEd

A multi-colored display would show whether districts, schools and student subgroups are or aren't meeting the state or locally defined target for each metric in the evaluation rubric, such as high schoolhouse graduation rates, access to career or college prep courses, performance on standardized tests. This shows a small portion of the data display of a draft evaluation rubrics proposed for the Country Board by the research agency WestEd.

The state constabulary says that the evaluation rubrics should serve several purposes:

- Help lease schools and school districts identify strengths and weaknesses;

- Help county offices of education, which must approve district LCAPs, place weaknesses that districts must deed on to prove comeback;

- Help the state superintendent of public didactics to place those districts that, having failed to ameliorate, require intervention.

The evaluation rubrics will function every bit both a guide for district cocky-improvement and a basis for determining outside intervention. The state board volition have to spell out how the ii purposes will mesh and how the rubrics volition help, not duplicate or conflict with, the LCAPs that districts spend months preparing. WestEd's typhoon rubrics include sections in which districts will be asked to analyze what is and isn't working and identify strategies and best practices they'll prefer.

The board must respond many questions in establishing metrics and establishing a procedure for holding schools answerable for meeting them. Amid them:

Should in that location be uniform evaluation metrics for all districts, or could districts devise them, based on their ain preferences and priorities?

Burr and Kirst said they'd be open to a mix of land and local metrics. Particularly in the areas of career readiness and student engagement, districts could serve as laboratories for experimentation, Kirst said. The civil rights coalition took a harder line in an analysis of a preliminary version of WestEd'south rubrics. "We believe the (Local Control Funding Formula) statute requires that the State Board establish uniform country performance and comeback standards. Anything less than uniform statewide standards would undercut, if not irreparably impair, meaningful accountability for ensuring equality of educational opportunity, improving student outcomes and endmost the achievement gap for all students."

What and how many measurements of school functioning will all districts and charter schools be held accountable for?

The land board could require lots of them. But lath fellow member Sue Burr, the lath'south liaison in the evaluations rubrics procedure, said she views the evaluations rubrics primarily as a tool for districts' self-assessment. For state accountability purposes, she favors holding districts answerable for perhaps no more than three metrics required in the evaluation rubrics. An accountability organization should non resemble a checklist under the No Child Left Behind law, she said. "We desire locals to embrace their responsibilities," she said. John Affeldt, managing attorney of the nonprofit law firm Public Advocates and 1 of the authors of the ceremonious rights coalition's analysis, agreed in principle but said the coalition hasn't yet taken a position on what would trigger intervention. "That'due south a separate chat," he said.

Who will determine what assistance schools that aren't improving should receive, and how much time districts should be given to meet a state target before technical assistance or more intrusive interventions are imposed?

Nether No Child Left Behind, schools that failed to meet proficiency targets were labeled Plan Improvement schools, which was next to impossible to escape from, and the federal authorities gave them a narrow choice of interventions. Schools resented the process. State board members and legislative leaders say they want a constructive procedure, starting with canton offices of education, which would review the districts' evaluation rubrics and advise forms of expertise and help. The civil rights coalition suggested a timetable of five to seven years for schools and pupil subgroups to make performance targets. But the requirement for "opportunity to acquire" metrics, like ensuring that students accept textbooks and qualified teachers, should be "absolute" and immediate, Affeldt said.

Should there exist one model of school accountability or local variations for charter schools, schools serving students at risk of dropping out or schools that focus on careers?

Seven California school districts already are creating their own novel school accountability arrangement, with a multiple-mensurate index, under a one-year U.S. Section of Pedagogy waiver from the No Kid Left Behind law. Called the Cadre districts and encompassing nigh a million students, the 7 would similar to continue to employ their measures, every bit long as they can show schools are improving, Cadre executive managing director Rick Miller said recently.

Role of a new country agency

A pocket-sized agency with a big mission will make the final determination on which schools and districts volition need assist and ultimately state intervention. Created two years ago with a $10 million initial budget, the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence held its start meeting on Wednesday. Information technology will determine which consultants, county offices and school leaders have the expertise in areas such equally parent engagement, career and technical education or working with English language language learners and then assign them to schools needing help. It also volition make up one's mind if a persistently low-performing school or district needs state oversight.

The Legislature signaled its intentions when information technology chose the agency's name. Information technology should be a place where districts go to collaborate for assistance and referrals; intervention should be the last resort, Simpson said. Burr, who is serving every bit the state lath's representative on the collaborative's five-member board, said its offset role should be a "repository of learning" that collects and disseminates all-time practices.

In writing the rules for intervention, however, the country board will besides determine when and how frequently the collaborative must accept a harder line on intervention.

When she talks virtually the new accountability model, Burr uses terms that have seemed strange during the era of No Kid Left Behind.

Ane is "trust." "We have a huge job to rebuild trust to say nosotros are serious nearly local accountability," she said. "We take to trust that local educators will do what is right on behalf of students they serve."

Some other is "patience." "Information technology volition take a long fourth dimension to build a coherent organisation in a meaningful way," she said.

Notwithstanding some other is "adaptability." "We need to build in self-reflection and examine goals and the evaluation rubrics every 5 years or then," she said. "We never did this with the API."

But what ane person views as needed patience, another person views as needless inaction. Ted Lempert, president of the advocacy group Children At present, said he worries that the pendulum may swing too far in response to past problems.

"There's no question our previous accountability system was flawed," he wrote in an e-mail. "There's as well no question that it shined a calorie-free on the achievement gap and was critical to the gains nosotros've seen amongst kids of colour over the last decade plus. In amalgam the new organization, California leaders shouldn't overreact to by flaws past shying away from the land's role in ensuring that all students and their progress are tracked each year."

That tension will shape what the next school accountability system looks like.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource's no-cost daily e-mail on latest developments in education.

Source: https://edsource.org/2015/moving-beyond-a-single-measure-of-a-school/75433

0 Response to "Moving beyond a single measure of a school"

Post a Comment